When I was younger, my friends and I would spend hours upon hours in the Michigan winters playing in the snow. One of our favorite games to play as a group was King of the Hill. We’d pile up snow as high as we could, and then half a dozen or so 10-to-12-year-olds would madly dash for the top of the snow mound, where the kid on top would have to stave off each and every wave of relentless and frenzied children for supremacy of the of the “hill.” While none of this impacts the White Sox directly, they can take a lesson from my friends and me: even when you are on top, you cannot afford to stop looking for ways to solidify your position, as your opponents are always seeking ways to dethrone the momentary king, in this case, the king of the American League Central Division. Any gap in the armor provides an opportunity for opponents to gain ground on the White Sox, and one such vulnerable area is the current catching situation.

When the White Sox signed Alex Avila this winter I was initially ecstatic. I assumed that the White Sox had just acquired another capable backup catcher who would provide some platoon relief for incumbent Tyler Flowers. I thought limiting Avila to a backup spot would both keep him healthy and improve his offense as he would be hitting more often with fresh legs. Then the next few days happened and much to my dismay Flowers was jettisoned by the White Sox which paved the way for Dioner Navarro to sign with the team and create the catching tandem with which Chicago opened the season.

Now, I understand what the White Sox brass probably had in mind when they acquired Avila and Navarro; that these moves would make the offense from the catcher position more palatable, and through that lens it does make some sense. Flowers had posted an uninspiring TAv of .245 over the 2014 and 2015 seasons combined, the White Sox as a team desperately needed more offense due to the many black holes employed by the offense (the Sox had yet to bring in Todd Frazier and Brett Lawrie), and the Avila (multi-year TAv of .265 against RHP) Navarro (multi-year TAv of .289 against LHP) tandem had strong, complementary platoon splits versus right handed and left handed pitching, respectfully. Unfortunately lost in the desire to bring on more offense was seemingly nary a concern for the erosion of Avila’s body from his previous years of abuse, and most importantly, a complete disregard for defense and the associated ramifications that would have on the pitching staff.

I can forgive the White Sox for overlooking the first of my two objections. Herm Schneider and company have done a wonderful job keeping White Sox players healthy over the years and this phenomenon has gone on for quite some time and by any measure can be considered a somewhat sustainable expectation (I can only assume that this has been accomplished by an underground pipeline that runs from U.S. Cellular Field to the United Center and somehow sucks all of the stem cells out of Derrick Rose’s knees, Taj Gibson’s ankles, and Joakim Noah’s feet for use in re-growing injured muscle and ligament tissue from White Sox players). And it’s worth mentioning that both Avila and Navarro hold strong reputations for pitch calling and staff management. However, I was completely miffed by the lack of concern regarding defense, namely catcher framing.

According to Baseball Prospectus’ framing numbers, during the 2015 Major League Baseball season, only two catchers, Yasmani Grandal and Francisco Cervelli, were worth more Framing Runs than Tyler Flowers and his 16.7 runs. Additionally, looking at StatCorner’s Catcher Report, Flowers was worth just over 22.5 runs above average with his framing in 2015 which ranked second in MLB to the aforementioned Cervelli. What I’m getting at is that even if you believe catcher framing is a somewhat subjective science, there’s probably merit to the numbers when two independent data sources come to the similar conclusion that not only was Flowers above average at stealing his pitchers an extra strike here and there, he was essentially among the league’s elite in this category. The same certainly cannot be said about Avila, -8.5 BP Framing Runs and -5.8 StatCorner runs above average, and Navarro, -3.3 BP Framing Runs and -4.1 SC runs above average, in 2015. Considering the White Sox primary backup catcher in 2015, Geovany Soto was just about average defensively, -0.6 BP Framing Runs and +5.6 SC runs above average, the projected defensive downgrade the White Sox made from 2015 to 2016 was, in total, massive.

Now, I’m not the first person to point out and critique the move from the defensive prospective. Patrick Nolan of South Side Sox talked about this in his review of the White Sox off-season. At face value, he argued, the moves looked like a sure downgrade from the White Sox, unless there was some sort of asymmetric information the White Sox had, like the ability to teach framing. I was hopeful that this might be the case, but so far in the new season, both Avila and especially Navarro have been quite awful at pitch framing with Avila posting -0.4 BP Framing Runs and -1.3 SC runs above average and Navarro at a staggering -4.7 BP Framing runs and -6.3 SC runs above average suggesting the White Sox have no such information. These numbers alone are quite concerning, but I believe they’re even more concerning when you consider the composition of the White Sox top heavy pitching staff.

The White Sox have two excellent starting pitchers in Chris Sale and Jose Quintana that I believe are not as susceptible to adverse effects from poor pitch framing as you average starting pitcher would be. They’re both well-established veterans with histories of excellent control and most importantly, their “stuff,” in my opinion, is good enough to the point where neither pitcher has to rely on nibbling at the corners of the strike zone in order to get batters out.

My best guess is that the White Sox front office held the same belief of these two players and that played heavily into their decision to punt catcher defense for offense. And unsurprisingly, these two pitchers have not really been impacted at all by the defensive downgrade at catcher as both of them are slicing through lineups like a lightsaber through a Skywalker appendage. But this is and was completely expected, and most projection systems pegged Sale and Quintana as (and this is a purely scientific term) friggin’ awesome, admittedly not to their current degree but I’d expect some natural regression, and still had the White Sox as a slightly above average team destined for 83 or 84 wins.

What I’m getting at is that I believe there should have been more thought given to maximizing the “unknowns” of the White Sox rotation and less concern given to lack of impact on the two “known” aspects of the rotation as the “unknowns” are the part of this equation that tip the scales toward playoff contention. Case in point: the White Sox were garbage last year and Sale and Quintana were still great. The reality is that improvement from all of the other players would be the engine that would make the playoff wheel turn. And the biggest potential for improvement was locked within the White Sox third starter Carlos Rodon.

Rodon flashed huge potential down the stretch last season, finishing the year on an eight-start run that saw him throw 54 and 2/3 innings to the tune of a 1.81 ERA, 3.61 FIP, 1.08 WHIP, and a 49:21 K:BB ratio while allowing only four home runs. Rodon was excellent during this stretch and non-coincidentally, in my opinion, all of this good work came after the White Sox made the decision to stop having Rodon pitch Geovany Soto and throw exclusively to Tyler Flowers instead. Flowers was exactly the type of catcher that Rodon needed. Though Rodon is extremely talented, he still has erratic control and is very prone to missing his spots.

When a pitcher is missing his spots, the home plate umpire almost always begins to squeeze the strike zone, which is especially problematic for a young starter who has enough trouble hitting the zone when it is fully operational. And whether it’s right or wrong for the home plate umpire to do something like this, having a catcher, like Flowers, who is able to tilt borderline strike calls, or at the very least preserve strike calls on pitches that should be strikes, is a huge countermeasure. Neither Avila nor Navarro have been able to do this, and according to StatCorner they currently hold staggering zone ball percentages (the percentage of pitches that are in the strike zone that are called balls) of 18.6% and 20.9% respectively, which is third-worst and worst among catchers with more than 500 pitches received in the 2016 season.

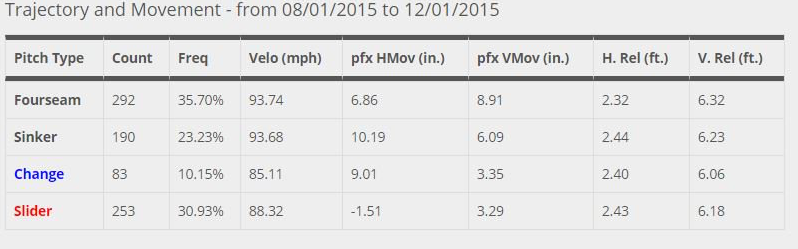

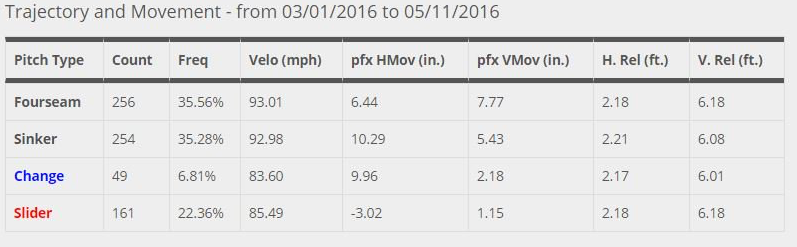

All of this suggests that Rodon’s security blanket is more than gone and this has most likely led to the regression from the form he was able to show down the stretch last season. The loss of a strong pitch framing catcher has had an additional side effect on Rodon. Pitch f/x data is showing a drastic shift in pitch mix and velocity from last August and September in comparison to this season. Below is the Brooks Baseball Pitch F/X data during the two snippets in time:

As can be seen, not only is Rodon using his off-speed pitches less frequently, his velocity is down across the board. Now, this is just me hypothesizing, but I would wager these changes are symptomatic of a pitcher sacrificing his best two assets (his slider and velocity) in order to throw strikes. It’s incredibly hard to say that that is caused directly by poor catcher framing, but the inability to get extra strikes for Rodon is likely a contributing factor that puts him behind in the count more often, and that limits the arsenal with which he can attack hitters. It also allows hitters to be more selective when facing Rodon which no doubt leads to fewer swings at his almost unhittable slider, further limiting Rodon’s effectiveness.

While I chose Rodon to showcase some adverse effects of the pitch framing, I don’t believe they are only impacting Rodon. Most mid-to-back end of the rotation starters only have one significant out pitch, and that, quite frankly, is why they are back end starters. This year for Mat Latos, it’s been his splitter, for John Danks, it had historically been his changeup, and we haven’t really seen much of Miguel Gonzalez but in years past it had been his slider. These guys don’t have three plus pitches like Chris Sale does, or two plus pitches like Jose Quintana does. Perhaps more importantly, they do not have dominant fastballs, and are more likely to nibble at the strike zone until they can get the batter into a count where he is more apt to swing out of the zone. This becomes much more difficult when the catcher is not adept at swaying umpires on borderline pitches.

Now, all this doom and gloom might make it seem like the White Sox are off to a terrible start in 2016. In fact, quite the opposite is true. Through 35 games, they’re 23-12 and have a five-game lead on the second place Cleveland Indians. With Avisail Garcia’s recent surge the offense is looking very solid. However, as I said above, any team on top of the division should always be cognizant of their Achilles’ heel and seek out ways to improve the situation. Currently, I believe the catching position is the biggest concern for the White Sox and is negatively impacting the other position of weakness for the Sox, the back end of the rotation. I don’t have a perfect solution for the Sox, but I do know that improving the catcher defense would go a long way toward pushing this team to the playoffs, while leaving it unchecked will continue to have adverse effects on the team.

Lead Image Credit: Brad Rempel // USA Today Sports Images

Even though i have my doubts on how much framing is calculated (How much is thanks to a skill of the catcher and how much is due to random subjective stuff) This is a sound article.