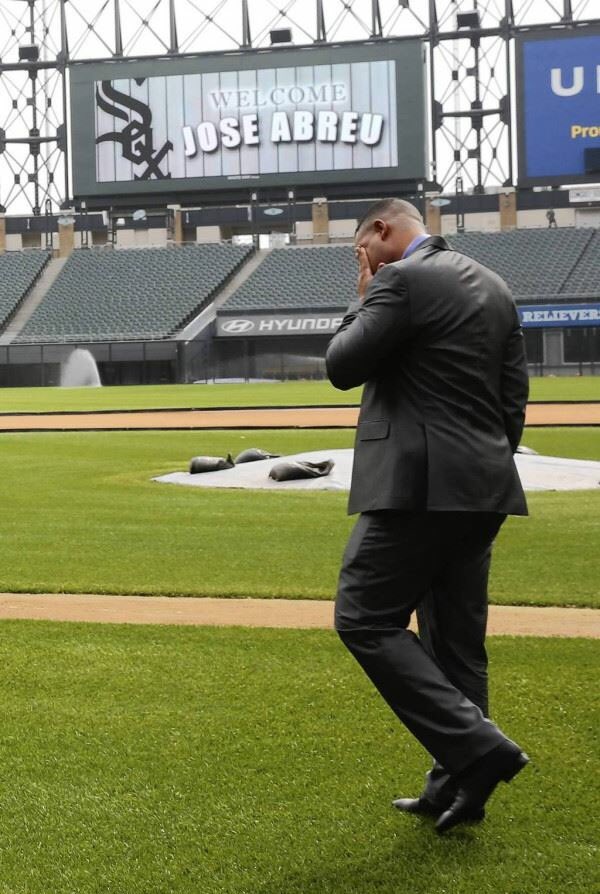

“I think about this photo a lot, the travels and trials of Jose Abreu and other Cuban players to come here.”

I have been thinking about this tweet, which is about thinking about this photo a lot, a lot on my own.

Jose Abreu‘s career trajectory is…implausible. His first presence in stateside baseball consciousness came as a hinted, looming monster still waiting to be discovered in Cuba after Yoenis Cespedes had arrived and electrified the league. Someone who has put up a .453/.597/.986 batting line in Cinefuegoes doesn’t sound like the type of player for whom the perpetually under-the-radar Chicago White Sox win the bidding.

Yet he arrived, after a harrowing trip out of Cuba with his family, on far too small of a boat to make the journey, and the typically murky process Cuban expatriates have to navigate to MLB free agency. The almost Late-90’s Bad Boy Records-style shiny suit Abreu wore to his introductory news conference remains the biggest misdirect he’s ever thrown at Chicago as to his personal nature.

Since then Abreu has been almost too perfect as a sports figure. His statements to the media are translated, so tone and nuance are often left behind, but they’re unflinchingly positive and humble. He defends manager Robin Ventura when the time calls for it, he smiles at American teammates’ clumsy attempts to connect, and is the type of player who launches sincere headlines like “Jose Abreu wants to learn English to sing the national anthem.” If it’s for show, he doesn’t take days off; he once said “I have always believed deep in my heart he will be a great player,” about Dayan Viciedo during the dog days of September 2014, just a couple weeks before Viciedo made his last appearance in an MLB game to date.

From what we know about the facades public figures put up, Abreu seems unknowable, because there’s nothing bad known about him. There are allusions to his personal turmoil, like having to leave his young son in Cuba when he defected, but they exist outside any prism where it’d be remotely appropriate to pass judgment. Insight into something truly divisive about Abreu, like whether these two years–two years since he was wiping tears away from his eyes while standing on the U.S. Cellular Field grass, astonished at how far he had come–have lived up to his expectations, seems more than unlikely to be revealed.

Abreu has stepped into the middle of a team in a rebuild, willing or not, dealt with an embattled coaching group, sagely stayed clear from the LaRoche flap, and has been more or less tasked to carry the offense by himself, while seeing his franchise attempts to put hitters around him at limited cost fall flat up to this point. Maybe he’s plenty satisfied to have the opportunity to play at the highest level and provide millions for his family, but maybe he’s noticed how much things are all on him too.

The White Sox are still the same team he was brought in to rescue the offense of in 2014. Abreu is not an asset they stacked, but an individual they have invested in. They’re the franchise that scoffs at Chris Sale‘s injury risk, cites Jose Quintana‘s character and calls him untouchable in trades, extends Adam Eaton off of one good season rather than let him go to arbitration. They don’t crank talent off an assembly line, they believe the guys they entrust to steward their franchise to be exceptions to the rules, and to drag the franchise above the holes and lack of depth on display elsewhere.

That one monster line from Cinefuegos action that we all quote is from 2010, when Abreu was 23-years-old. He had been trending down from that unimaginable peak when the Sox signed him, and trends for power production and his unremarkable athleticism–relatively speaking–suggest a player who, even while very productive, could have already played his best ball, and will find seasons like 2015 where nagging aches and pains sapped away at his ability for weeks on end, increasingly normal.

But the Sox roster, nay, the franchise, simply isn’t built for Abreu to be a garden-variety first division first baseman, or at the fringes of All-Star level depending on health. There just isn’t that level of offensive depth on an MLB-level to pick up the slack, nor a reservoir of talent bubbling underneath. With the Cuban talent market’s value having exploded well beyond where it was when he was signed, and the White Sox avoidance of big free agent expenditures, there’s no clear path for the Sox to even land a talent of Abreu’s caliber again.

The Sox are built on the idea that Abreu is truly special and generational: a man with 35+ home run raw power and batting champ level pure hitting ability, someone who can combine the fearsome onslaught of his first three months in the league with the infinite skill of the man who hit over .400 during a 18-game homer drought in the second half of 2014. As much as his career already comes off as an idealistic triumph over unimaginable odds, Abreu needs to find another level.

Is it too much to ask? Probably, but there’s no one with whom it would be better to try.

Lead Photo Credit: David Banks // USA Today Sports Images

Speaking of sluggers….and miracles.

Why didn’t the WhiteSox claim Jesus Montero who went to the Jays (Very low in the waiver’s priority list). Montero has a lot of problems at the majors, but he did have a nice year in the minors last year.

The minor league numbers for Montero don’t matter a ton since he was older than most of the competition and was hitting in the offensive friendly part of the PCL.

Even though the Sox could use help at DH, that’s literally the only position he can play and hasn’t shown anything against major league talent.

i thought about that too. he’s actually partially played in the major leagues in 5 different season (even 135 games in 2012). if you go from playing that many games in 2012 to 29 to 6 to 38, i’m assuming something’s up. maybe it’s the .215 batting average over the past 3 seasons? or worse yet, the .295 on base percentage? since he’s a right handed hitter, is he any better (or worse) than avisail?

Beautiful article Fegan. Let’s hope he gets some protection this year.